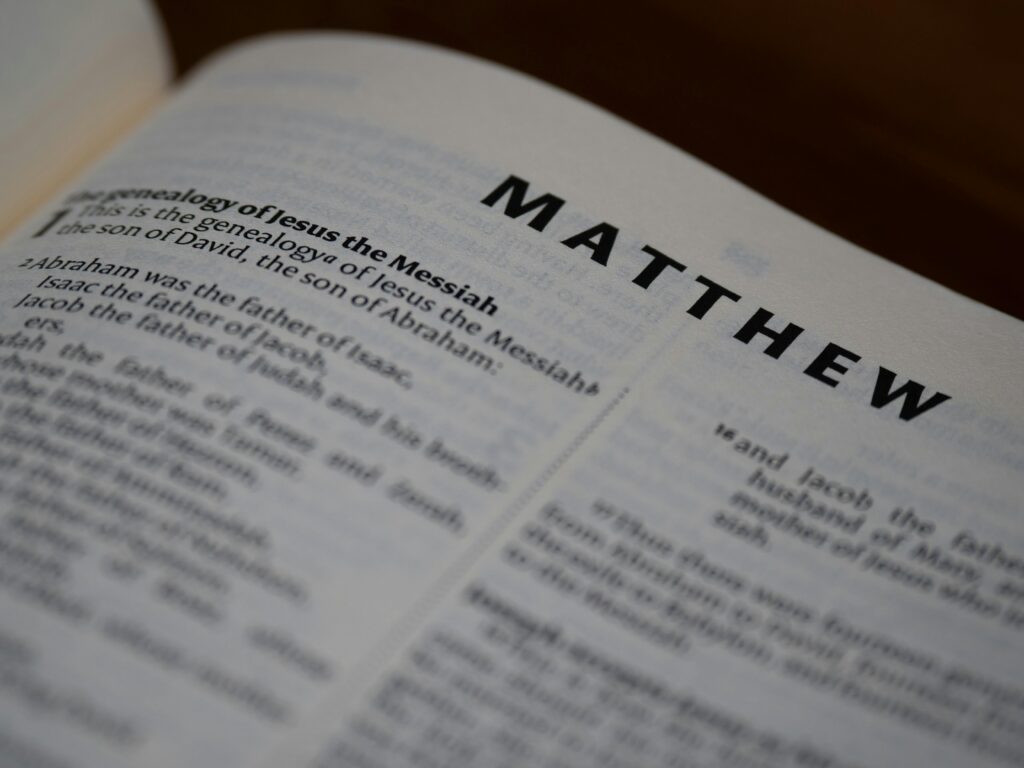

Bible readers, upon opening the New Testament, encounter the long list of names that begins the Gospel of Matthew and we work our way through them not really taking them in. It is a common experience to find such genealogies challenging or indeed uninteresting but I always try to remain mindful of the fact that everything in Scripture is there for a reason, even if we don’t grasp or understand it so, we should pay attention even in the “boring” bits.

The discovery of a second, different list in the Gospel of Luke can then create a sense of confusion, or even concern about a contradiction – why does the Bible contain two contrasting family trees for Jesus? However, rather than presenting a contradiction, these distinct genealogies offer a profound invitation to a deeper understanding of the roles of Christ. These differing family lines are not historical errors but deliberate theological statements, each carefully constructed to reveal a unique and essential aspect of just who Jesus is, to the differing readers of the times.

The early church historian Eusebius of Caesarea, writing in the fourth century, acknowledged this puzzle, noting that the two lists have been a subject of inquiry for many, yet he firmly believed a harmonious explanation existed.

The most immediate difference lies in their starting points. Matthew, whose Gospel is deeply rooted in a Jewish context, begins with a powerful declaration: “This is the genealogy of Jesus the Messiah, the son of David, the son of Abraham” (Matthew 1:1).

⚠️ This opening is profoundly significant.

By tracing the lineage from Abraham, the father of the Jewish nation, Matthew firmly places Jesus within the narrative of Israel. He is presented as the ultimate fulfilment of the covenant promises God made to Abraham, that through his offspring all nations on earth would be blessed (Genesis 12:3, 22:18). And also, by identifying Jesus as the “son of David,” Matthew underscores his royal claim to the throne of Israel, directly addressing the Jewish expectation of a Messiah from David’s line, as prophesied in scriptures such as Isaiah 9:7 and Jeremiah 23:5.

Now, in stark contrast, the Gospel of Luke takes its readers on a far grander journey backwards through time. His exploration of Jesus’ genealogy moves in reverse order, starting from Jesus and working back through time, past Abraham and Noah, all the way to “Adam, the son of God” (Luke 3:38). This is a breath-taking shift in perspective.

For, while Matthew anchors Jesus in the history of a specific people (Israel), Luke expands the canvas to encompass the whole of humanity and you may also be reminded here of Luke 2:29-32:

📖 Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word:

For mine eyes have seen thy salvation,

Which thou hast prepared before the face of all people;

A light to lighten the Gentiles, and the glory of thy people Israel.

By connecting Jesus to Adam, Luke presents him not merely as a Jewish Messiah but as a universal Saviour for the entire human race, all of whom share Adam as their common ancestor. This resonates deeply with Luke’s overall emphasis on Jesus’ compassion for outsiders, Samaritans, and Gentiles, highlighting that the good news is for all people (Luke 2:10).

Let’s look a little closer now and consider the most critical divergence between the two lists, which occurs in the generations following King David. It is here that the paths split, and understanding this split is essential. Matthew, emphasising Jesus’ legal right to David’s throne, follows the royal line of succession. He traces the ancestry through David’s son, Solomon, and continues down through the kings of Judah, including figures like Rehoboam and Hezekiah (Matthew 1:6-7). Through this kingly list Matthew writing under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, delivers this genealogy in such a way that it highlights how Jesus meets both the political and messianic expectations of his Jewish readers.

Luke, however, chooses a different path. He traces the lineage of Jesus through another son of David named Nathan, who is mentioned in the Old Testament but is not part of the royal kingly line (Luke 3:31; cf. 2 Samuel 5:14). A compelling reason for this choice involves a particular king found in Matthew’s list: Jeconiah (also known as Jehoiachin). The prophet Jeremiah pronounced a severe curse upon this king, stating, “Record this man as if childless… for none of his offspring will prosper, none will sit on the throne of David or rule anymore in Judah” (Jeremiah 22:30). If Jesus were a biological descendant of Jeconiah, this curse would present a significant theological problem for his claim to the Davidic throne.

This apparent problem finds its solution in the nuanced role of Joseph, with the two genealogies working in concert. In Jewish law, a father’s legal lineage and rights were passed to his son through a formal declaration of paternity, regardless of biological connection. This in important to understand as Matthew is careful to state that Joseph was the husband of Mary, and that Jesus was born of her before they had come together (Matthew 1:16, 18). He then explicitly places Joseph in the Solomonic, kingly line by calling him the son of Jacob (Matthew 1:16). This establishes Jesus’ l**egal right to the throne of David through his adoptive father**.

💥 As the legally recognised son of Joseph, Jesus inherits the royal title without inheriting the bloodline curse associated with Jeconiah.

This naturally leads to the question of whose lineage Luke provides. The most ancient and widely held explanation, supported by early church historians, is that Luke presents the genealogy of Mary. The phrasing in Luke is telling: “Now Jesus himself was about thirty years old when he began his ministry. He was the son, so it was thought, of Joseph, the son of Heli” (Luke 3:23). The qualifying phrase “so it was thought” is a careful distinction. If Joseph is the “son of Heli” only by law or marriage, then Heli is most naturally understood as Mary’s father.

This view is corroborated by the early church father, John Chrysostom, who in his Homilies on Matthew, argued that Luke’s genealogy is that of the Virgin. Therefore, Jesus is described as the biological grandson of Heli (Luke 3:23) through his daughter, Mary. This would mean Luke is tracing Jesus’ bloodline from David through Nathan, a line untouched by the curse on Jeconiah. This genealogy confirms Jesus’ genuine, biological descent from David, while Matthew confirms his legal and royal standing.

Beyond the central divergence at David, other differences highlight the specific intentions of each writer. Matthew structures his genealogy with a clear pattern, organising it into three sets of fourteen generations (Matthew 1:17). This mnemonic device (probably based on the numerical value of David’s name in Hebrew) makes the list memorable and reinforces the idea of divinely orchestrated history.

It’s important to note that in order to achieve this symmetry, Matthew deliberately omits several kings from the historical record found in the books of Chronicles (cf. 1 Chronicles 3:11-12). For instance, between Joram and Uzziah (Matthew 1:8), he skips Ahaziah, Joash, and Amaziah. This was a common practice in ancient genealogies, where the focus was on establishing a meaningful lineage rather than providing a comprehensive list.

Furthermore, Matthew’s inclusion of five women namely; Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba, and Mary (Matthew 1:3, 5, 6), was highly unusual in a patriarchal genealogy. Each of these women has a story marked by scandal, foreignness, or extraordinary faith and so their inclusion signals a key theme of Matthew’s Gospel: that God’s redemptive plan works through the unexpected and the outsider, foreshadowing that the coming of Jesus is good news for all people.

Here’s the thing though, wen you view these two lists together, both these “genealogies” form a harmonious and rich portrait of the role of Jesus to all peoples, not just Israel. They are complementary narratives, not competing accounts.

Matthew’s list presents Jesus the King, the legal Messiah of Israel, the fulfilment of specific Old Testament prophecies. Luke’s list presents Jesus the Saviour for all humanity, the second Adam who comes to redeem the entire human race.

The very existence of these two family trees tells us that Jesus is both the specific fulfilment of a promise to Israel and the universal answer to the deepest need of humankind. He is both the King of Israel and the Saviour of the World.

So, next time you encounter those lists of names at the start of Matthew and Luke, pause for a moment. See them for what they are: a profound and beautifully crafted introduction to the unique and world-changing person of Jesus Christ.