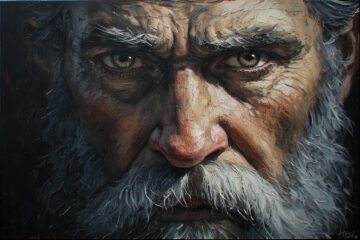

I stood in the bright sunlight of deepest Norfolk, my friend David had walked slightly ahead to the reception area, a place as far from my theological home as I could imagine. Before me was the Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham. A gnawing sense of trepidation, a legacy perhaps of the last 10 years spent in Reformed circles, whispered that this was a “Marian rabbit hole” I should avoid. I was a man who had built his faith on the bedrock of God’s absolute sovereignty and the doctrine of election. Yet, here I was, drawn to a place that represented everything my tradition viewed with suspicion. This pilgrimage was the culmination of a six-month journey from a system of beautiful, intellectual certainty to a world of sacramental mystery, where grace feels less like a decree and more like a living, breathing presence.

The Foundation: A World of Sovereign Grace

For years, my theological compass was calibrated by the majestic doctrine of God’s sovereignty. It provided a coherent, powerful framework where God’s electing grace was the uncontested engine of salvation. Within this system, the Eucharist was a solemn and meaningful memorial – a symbolic representation of Christ’s once-for-all sacrifice, but not His actual body and blood. The Virgin Mary was a secondary player, a faithful but passive vessel, a willing pawn in the divine game of redemption. It was a tidy system, and I was, as some may know, a hardened drum-banger for it.

The Crack in the Foundation: When Scripture Broke the System

But the tidiness began to fray at the edges. How could I hold the profound truth of Ephesians 1 that God “chose us in him before the foundation of the world” alongside the equally clear declaration of 1 Timothy 2:4 that God “desires all people to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth”? Was it an either/or? My Reformed tradition had its answers, but they began to feel like a logical resolution that did not do justice to the full breadth of Scripture. This tension led me to explore older paths, listening to podcasts and reading works that engaged with the Catholic and patristic tradition. I was searching for a way to hold the tension, not just resolve it.

The Key That Unlocked the Door: Mary’s ‘Yes’

It was in the Annunciation that I found a key. I read Luke 1 not as a simple historical account, but as a paradigm of how God’s grace operates. The angel Gabriel announces God’s sovereign plan, but he does not impose it. He invites. He waits. And a young girl, full of grace, responds: “Behold, I am the servant of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word” (Luke 1:38, ESV).

This was not the action of a pawn. This was the ultimate example of synergy, the cooperation between divine initiative and human freedom. God’s grace was the primary actor, but it did not override Mary’s will; it elevated and cooperated with it. Her “Yes” was the necessary human response that ushered in the Incarnation. I began to see what the Church has always known: to honour the Theotokos, the God-bearer, is to defend the shocking reality of the Incarnation itself. The principle of lex orandi, lex credendi (the law of prayer is the law of belief) became clear. The Book of Common Prayer’s collects for Marian feasts aren’t eccentric additions; they are profound theological statements about how God chooses to work with his creation.

The Feast of Faith: ‘This IS My Body’

This new lens radically altered my view of the Eucharist. If God could take on human flesh from the willing Virgin, could He not give us His very life under the forms of bread and wine? I returned to Jesus’ words with fresh eyes: “This is my body” (Matthew 26:26, ESV). He did not say, “This represents my body,” or “This is like my body.” The Church Fathers, like St. Ignatius of Antioch, called the Eucharist “the medicine of immortality.” It was not a symbol to be remembered, but a reality to be received. The shift from a memorial to a Real Presence was the sacramental answer to my intellectual problem. Here, God’s grace became tangible, effective, and daily – an “effective continual movement,” as I now think of it, offered to all who approach in faith.

Walsingham: Journey’s End and Beginning

And so I found myself in Walsingham. The initial discomfort gave way to a profound peace. I saw the community not as crazy idolaters but as fellow pilgrims saved by grace through faith, gathered around the one whose “Yes” made our salvation possible. I realised I had only ever seen Mary as the Theotokos in a perfunctory, positional sense. At Walsingham, I understood her as the incarnational vehicle of grace, the first and model Christian. This place, perhaps what would have once been a source of unease, has become a home, a place of retreat to be nourished for the journey ahead.

Common Ground at the Foot of the Cross

To my Reformed friends, I say this: our common ground remains, and will always be, Jesus Christ. It is at the foot of the cross where we all meet. This journey has not been a rejection of God’s sovereignty, but a desire to see it operating more generously and mysteriously than I had ever dreamed. It is a desire to embrace the fullness of a faith that holds mystery in tension and sees God’s grace, sovereign, efficacious, and sacramental at work in every atom of creation and in every faithful “Yes” of his people.

Let us pray.

O Lord Jesus Christ, who by your birth at Nazareth didst sanctify the home of thy blessed Mother Mary, and by thy presence at the wedding in Cana didst raise marriage to the dignity of a sacrament: Mercifully look upon our families and our communities, and grant that by following the example of the Holy Family, we may come to the eternal joy of thy home in heaven; who with the Father and the Holy Spirit liveth and reigneth, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

(Adapted from the Walsingham Pilgrim’s Prayer)